Computational Design of Rubber Balloons

M. Skouras, B. Thomaszewski, B. Bickel, M. GrossProceedings of Eurographics (Cagliari, Italy, May 13-18, 2012), Computer Graphics Forum, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 835-844

Abstract

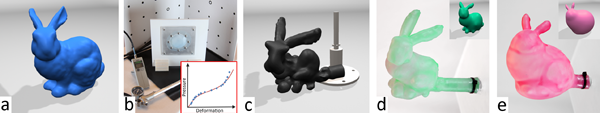

This paper presents an automatic process for fabrication-oriented design of custom-shaped rubber balloons. We cast computational balloon design as an inverse problem: given a target shape, we compute an optimal balloon that, when inflated, approximates the target as closely as possible. To solve this problem numerically, we propose a novel physics-driven shape optimization method, which combines physical simulation of inflatable elastic membranes with a dedicated constrained optimization algorithm. We validate our approach by fabricating balloons designed with our method and comparing their inflated shapes to the results predicted by simulation. An extensive set of manufactured sample balloons demonstrates the shape diversity that can be achieved by our method.Overview

Inflatable balloons are fascinating objects that attract the attention of both children and adults. Especially rubber balloons are commercially very successful, be it for toys, advertisement or decoration. A primary reason for their crosscultural ubiquity lies in the ease of manufacturing: the balloon mold, similar in shape to the inflated balloon, is briefly dipped into liquid rubber, e.g., latex. The rubber is then cured, removed from the mold—and the balloon is ready to deploy. This process is simple, efficient, and inexpensive, making it ideal for commercial production. But although more complex shaped molds could be used to obtain a wider range of balloon shapes, manually designing a mold that yields a complex inflated shape is a formidable task. For this reason, we mostly see rubber balloons of simple shapes such as ellipsoids, wavy tubes, or hearts. Foil balloons, by contrast, can be produced with complex shapes such as those seen in Macy’s annual Thanks Giving parade. But besides the fact that foil balloons are more difficult to fabricate, they do not stretch noticably during inflation. Nevertheless, it is primarily the extreme deformations that create the unique experience of inflating a rubber balloon.

The goal of this work is to develop a method for designing balloons that, once fabricated, can be inflated into as complex shapes as foil balloons but are as deformable and as easy to manifacture as conventional rubber balloons. Our approach consist in modifying the balloon rest shape which enables us to approximate a wide range of target shapes with constant thickness material and also allows us to use a simple dip molding process for fabrication. This together, we believe, is the enabling technology for practical fabrication of custom-shaped rubber balloons.

In summary, we present a method for automatic design and easy fabrication of balloons that can be inflated into desired shapes, including parameter acquisition, computational modeling, shape optimization and physical fabrication.

Results

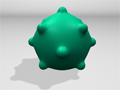

In order to explore the capabilities of our method we experimented with a variety of different target shapes. For each example, we computed an optimized rest shape, printed corresponding molds and fabricated the balloon using silicone. For comparison, we also fabricated balloons corresponding to the downscaled target shapes. Fig.2 shows our results in a compact overview.

The last column clearly indicates that the downscaled targets do not lead to acceptable approximations. Indeed, the original shape is indiscernible in most cases. By contrast, the simulated shapes of the optimized balloons (col. 3) as well as the fabricated counterparts (col. 4) are in good agreement with the targets for the majority of the examples and most of the characteristic features are clearly discernible.